All Aboard!

Argentina's mighty trains and the birth of a fine nation...

Qué lento corre el tren

más corre mi ansiedad,

Qué cosas me dirás, qué cosas te diré,

Qué lento corre el tren qué ganas de llegar.

How slow the train goes,

My anxiety runs faster.

What will you tell me, what will I tell you?

How slow the train goes, I can’t wait to arrive.

~ Qué Lento Corre El Tren (How Slow The Train Goes) by Enrique Rodríguez with Armando Moreno (1943)

Joel Bowman with today’s Note From the End of the World: Buenos Aires, Argentina...

All trains ultimately arrive at the same terminus. From the mightiest empire to the worthiest currency to the battiest ideology; eventually, the tracks eventually run out for us all.

By the time the last shot was fired in The Great War (WWI), much of the geopolitical map of continental Europe had been redrawn. The Ottoman, Austro-Hungarian and German Empires laid in ruins, while the Kaiser’s abdication in Germany also marked the end of the Hohenzollern dynasty's 300-year rule of Prussia. For the victors and the vanquished alike, the cost of the various military campaigns were staggering, both in terms of capital expenditure, foregone industrial opportunity and, most precious of all, human life.

Long Train Runnin’

Meanwhile, down here at the other End of the World, Argentina emerged from “The War to End All Wars” at the very height of her wealth and power. Emblematic of its position as a titan of global trade, the nation’s vast railway network stretched to the farthest reaches of the country. Not unlike the trains of the great American west, the Argentine rail helped create and connect far-flung locales and allowed a growing population to expand into remote parts of a rich and varied land. (Today, Argentina is the world’s 8th largest country by landmass).

Of course, trains do not roll along tracks built by lofty intentions and empty political promises alone. Such an impressive infrastructure achievement required the usual real world inputs, too: time, capital, ingenuity and a friendly enough market to encourage investment and foster growth.

Happily, during the project’s early years, Argentina enjoyed just such circumstances... even if that would not always be the case. For better and worse, it is no exaggeration to say the rise and fall of Argentina’s mighty train network closely mirrors the nation’s trajectory, both politically and economically. To see where the nation might be headed in the future, therefore, it might be worth taking a look at whence it has come.

The Argentine railway project began as an undertaking of “national independence” shortly after the nation’s Constitution was drafted, in 1853. Indeed, as none other than Juan Bautista Alberdi himself wrote in his foundational work Basis and starting point for the Political Organization of the Argentina Republic (1928), on which the nation’s Constitution was based, “the railway is the means of turning around what the colonizing Spaniards did on this continent.”

Thus it was that through a series of private investments and public land concessions, Argentina’s “Big Four” railway companies were formed in the mid- to late-19th Century: The Pacific and Western, Buenos Aires Western, Central and Great Southern Railway Companies. (Similar in kind to the Cleveland, Cincinnati, Chicago and St. Louis Railway companies, or CCC&StL, in the United States of America.)

Runaway Train

It is perhaps worth noting here that it was due largely to the economic policies of Argentina’s President Bartolomé Mitre – a classical liberal, or what today might loosely be called ‘libertarian’ – which led to the state-owned railways being sold off to foreign (mostly British) companies toward the end of the 19th Century.

Predictably, the sales of these public assets prompted some anti-British sentiment among the newly-independent Argentines, who criticized the move as being “unpatriotic.” Nevertheless, it was this critical influx of foreign private capital that ultimately allowed for the enormous expansion of the domestic network, which in turn proved a major catalyst for Argentina’s economic growth over the ensuing decades.

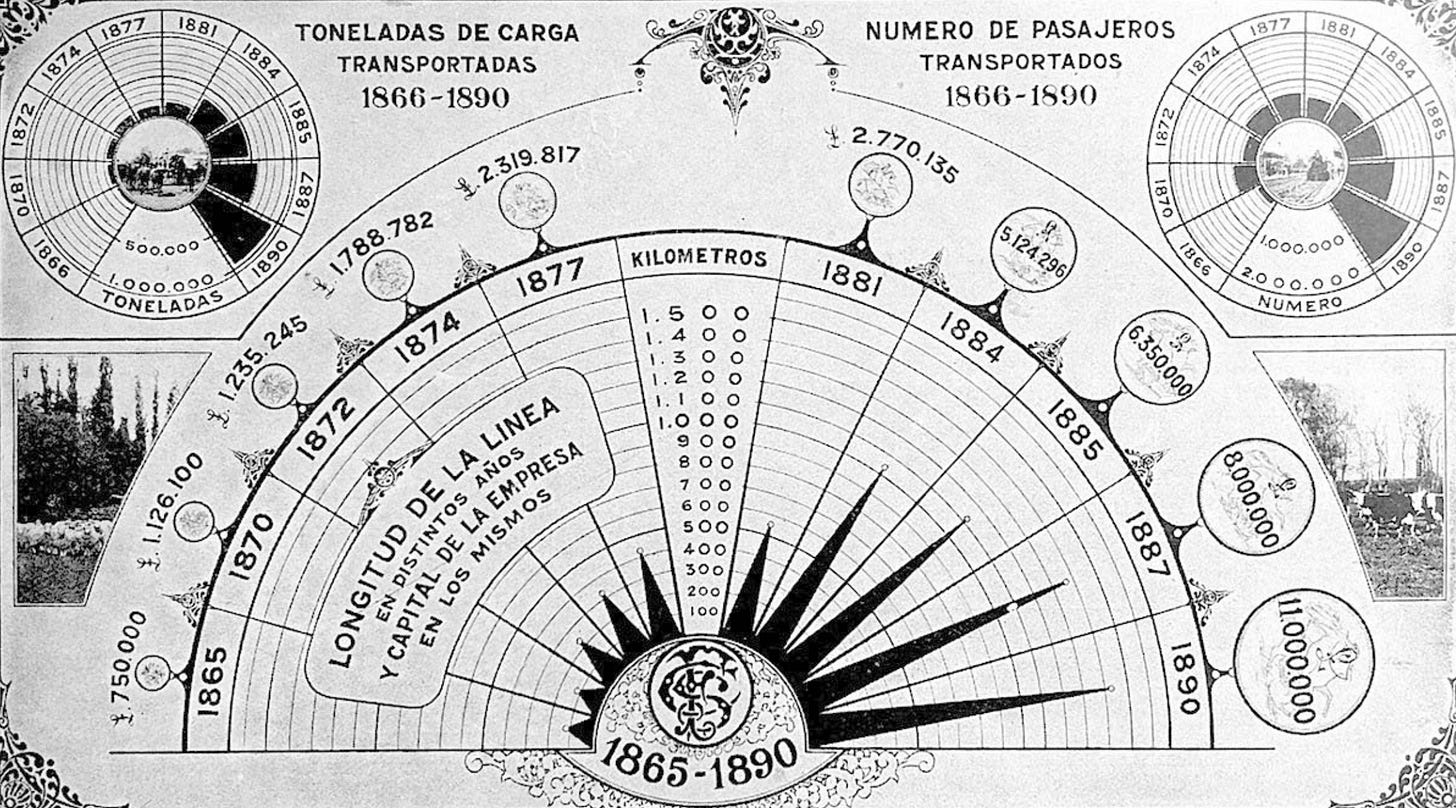

To wit, in 1880, Argentina’s total railway system measured just over 2,500kms (1,500 miles); by the turn of the century, it had reached 16,500 kms, and by the end of the war, in 1920, some 47,000 kms of track reached out across the vast land. In terms of passengers, the trains went from carrying 3 million people in 1880, to 18 million in 1900... to 147 million in 1920. So too for freight. Where in 1880 the trains carried 1M tonnes of cargo, they hauled 11.8M tonnes in 1900...and 45.5 million in 1920.

Backbone of a Nation

So from the towering Andean mountains in the west, the distant borders with Bolivia and Paraguay in the north, and across the mysterious Patagonian region in the south, Argentina’s mighty railway transported the country’s abundant natural resources across her Pampas to the capital port city, here on the banks of the Rio de la Plata, where it was shipped to the distant corners of the globe. Along with foreign investment, mostly from Britain and France, and a massive expansion in European immigration, Argentina’s world-beating export trade of livestock, grains and raw materials translated into an unprecedented economic boom down at the End of the World.

During the period from 1880 to 1905, annual GDP growth averaged about 8%, resulting in a 7.5-fold growth of the economy overall. On a GDP per capita basis, Argentina went from 35% of the United States average to roughly 80% over the same quarter century. And by the time the Roaring ‘20s swung into action, los Porteños, as the metropolitan “port people” are known here, counted themselves among the richest cosmopolitans in the world.

Today, a casual stroll down Buenos Aires’ dramatic boulevards – Av. Libertador, Av. de Mayo, Av. 9 de Julio – reveals a veritable cornucopia of architectural treasure from her glorious Belle Époch era. (Do remind us to send you a flâneur video from the rooftop of the magnificent Palacio Barolo (1919) one of these weekends.) And undergirding this vast wealth, the emblematic railway system, backbone of the nation’s trade, pride of her industrious people.

Alas, Argentina’s mighty railroads would eventually run out of track... just as we have run out of space, at least for today.

Stay tuned for your next Note From the End of the World...

Cheers,

Joel Bowman

P.S. Happily for liberty lovers (and train enthusiasts!), freedom is in the ascendency in many places around the world, including right here in Argentina.

In fact, it seems like barely a day goes by down here at the End of the World where some nonsensical collectivist weed is not uprooted. And slowly but surely, people are catching on, thanks in large part to independent reporting.

Right here on Substack, for instance, tens of thousands of independent authors, journalists, investigators and opinion columnists are sharing their own perspectives on everything from politics to economics, financial markets to crypto investing, corporatist malfeasance and individual triumphs alike.

We may be small… but we are legion. And we are bringing down the mainstream narrative… one brick at a time.

As always, we are especially grateful to our generous Notes members, whose dues allow us to pursue this humble publication. If you would like to join our growing Notes community and help support the ideas of free markets, free minds and free people, please consider becoming a member today. Thanks in advance ~ JB

What I find most interesting is how the Argentines have moved beyond "fairness doctrine". They are fed up enough with it that they tried something entirely new. They were willing to give up their government free lunch promise and bet on a new idea. Less government. My suspicion is the young and indoctrinated college graduates in the US are moving dow the road of Marxism, which sounds great. Will it be 100 years before America dumps the government support and chooses their own motivation of each individual?

I hope you continue this story. Is the rail system still viable, or did it fall to the ravages of collectivism, like in the US (amtrak, anyways)? (Well, I think we all know the answer to that one.)