The nature of peoples is first crude, then severe, then benign, then delicate, finally dissolute.

~ Giambattista Vico

Canon Fodder

By Joel Bowman

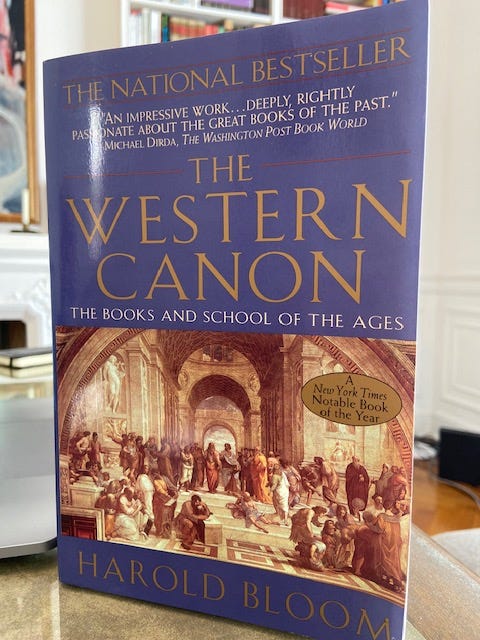

When he set out to compose his own magnum opus, The Western Canon, The Books and School of the Ages, the man many considered to be the world’s greatest living reader faced a task even the eponymous hero of his beloved Odyssey would have found daunting. By the early nineties, Harold Bloom (1930-2019) had been Professor of Humanities at Yale University for as long as anyone could remember; certainly long enough to know that any attempt to assess the literature of the ages by pure aesthetic value would be met with Charybdian howls and Scyllian gnashing of teeth, especially from those he referred to as the “School of Resentment.”

But for Bloom, for whom it could almost have been said there was “nothing left but to reread,” the labor was one of unadulterated love. To hear him describe the art of deep reading (especially of poetry) is to listen to man himself enraptured, whose cumulative decades of reading had suspended him somewhere between the world of the living, breathing, flesh-and-blood humans who sought his opinions, his attentions, his contributions, and the parallel, though no less crucial to him, worlds of Shakespeare, Dante, Goethe, Shelley, Cervantes, Ibsen, Joyce...

Infinite Time

If mortality did not concern us, reasoned Bloom, if we truly dwelled among the Gods, there would be scant need for us to be so judicious in our reading selection, to jettison the trendy in favor of the time-tested, to allow for fleeting considerations other than true aesthetic merit. Writes Bloom:

What shall the individual who still desires to read attempt to read, this late in history? The Biblical three-score and ten no longer suffice to read more than a selection of the great writers in what can be called the Western tradition, let alone in all the world’s traditions. Who reads must choose, since there is literally not enough time to read everything, even if one does nothing but read. Malarmé’s grand line – “the flesh is sad, alas, and I have read all the books” – has become a hyperbole.

This from a man who could read 400 pages in an hour, without sacrificing comprehension. Someone, who had not only learned Shakespeare’s poetry by heart, but who appeared sometimes to dwell himself among the Bard’s cast of characters, and whose students used to challenge him by quoting Milton’s Paradise Lost, mid-sentence, and then watching, entranced, as he picked up the thread and followed it until the end of Yale’s quads without breaking his stride. The Englishman’s epic stands at just beyond 10,000 lines. Bloom, seemingly, stood amidst them all.

In marshaling the 26 writers he considered to be at the core of The Canon, Bloom followed in Joyce’s Wake (Finnegans, that is) and looked to the above-mentioned Italian philosopher, Giambattista Vico (1688-1744), for inspiration. In his New Science, Vico had posited a cycle of phases to explain the course of history – Theocratic, Aristocratic, Democratic and Chaotic, out of which a new Theocratic Age would emerge. Bloom commences his own Aristocratic Age with Shakespeare, “because he is the central figure of the Western Canon.”

Herewith, Harold Bloom’s Twenty Six...

William Shakespeare

Dante Alighieri

Geoffrey Chaucer

Miguel de Cervantes

Michel de Montaigne

Molière

John Milton

Samuel Johnson

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

William Wordsworth

Jane Austen

Walt Whitman

Emily Dickinson

Charles Dickens

George Eliot

Leo Tolstoy

Henrik Ibsen

Sigmund Freud

Marcel Proust

James Joyce

Virginia Woolf

Franz Kafka

Jorge Luis Borges

Pablo Neruda

Fernando Pessoa

Samuel Beckett

Aside from the tawdry, now almost compulsory “representational” criticisms of The Canon, namely that it ought to be based on arbitrarily selected demographics rather than aesthetic merit, perhaps the pettiest attack is that it presents a poor or wayward moral, social, political, etc. compass. Bloom himself preempts this assault in his elegiac opener, drawing attention to the undeniable and under-celebrated fact that, “The West’s greatest writers are subversive of all values, both ours and their own.”

Know Thyself

It is not within the works themselves that we search for guidance on such “real world” matters, in other words, but in the private dialogue they inspire us to conduct internally, something akin to what Socrates would have called the inner voice, or “Daemon.” Writes Bloom:

Scholars who urge us to find the source of our morality and our politics in Plato, or in Isaiah, are out of touch with the social reality in which we live. If we read the Western Canon in order to form our social, political, or personal moral values, I firmly believe we will become monsters of selfishness and exploitation. To read in the service of an ideology is not, in my judgment, to read at all. The reception of aesthetic power enables us to learn how to talk to ourselves and how to endure ourselves. The true use of Shakespeare or of Cervantes, of Homer or of Dante, Chaucer or of Rabelais, is to augment one’s own growing inner self. Reading deeply in the Canon will not make one a better or a worse person, a more useful or more harmful citizen. The mind’s dialogue with itself is not primarily a social reality. All that the Western Canon can bring one is the proper use of one’s own solitude, that solitude whose final form is one’s confrontation with one’s own mortality.

For the mere mortals among us, who lack access to a Bloomian photographic memory and fall well short of Malarmé’s hyperbolic lamentation, “confrontation with one’s own mortality” seems a perfectly suitable rationale to undertake a canonistic approach to deep reading. And once we have examined and reexamined all the stars in that bright sky, there’s always Bloom’s quartet of appendixes, which guide us through Vico’s Theocratic, Aristocratic and Democratic Ages, into our Chaotic present, before launching boldly into the Canonical Prophesy beyond.

Happy reading.

Joel Bowman

Next time you should address Bloom's list of the must read Ancient texts...

How Bloom could include in his “Top 26” Virginia Woolf but not Mr. Dostoyevsky should trouble readers who still peek at such lists—albeit with one eye closed. But with regard to Bloom they might not bother at all after reading Joseph Epstein’s devastating put-down of the Yale celebrity more than twenty-years ago (at https://bit.ly/3EWbbDy, and appearing again in Epstein’s collection “In a Cardboard Box: Essays Personal, Literary, and Savage” {2007]). If while “under the influence” I were to step back from my aversion to lists and rankings long enough to name my own “Starting Five” of America’s best literary critics of the past hundred years, Epstein would make the cut, but not Bloom. And if writing with great humor were given the weight it deserves, then Epstein would be the point guard on that squad.

An aside: have you read any of the books of your countryman the philosopher David Stove? A funny and incisive man who died before he got the attention and admiration he most assuredly deserved!